Top of the WorldJeff Glasbrenner takes Everest

By Michael Roberts

Photos courtesy of Team Glas

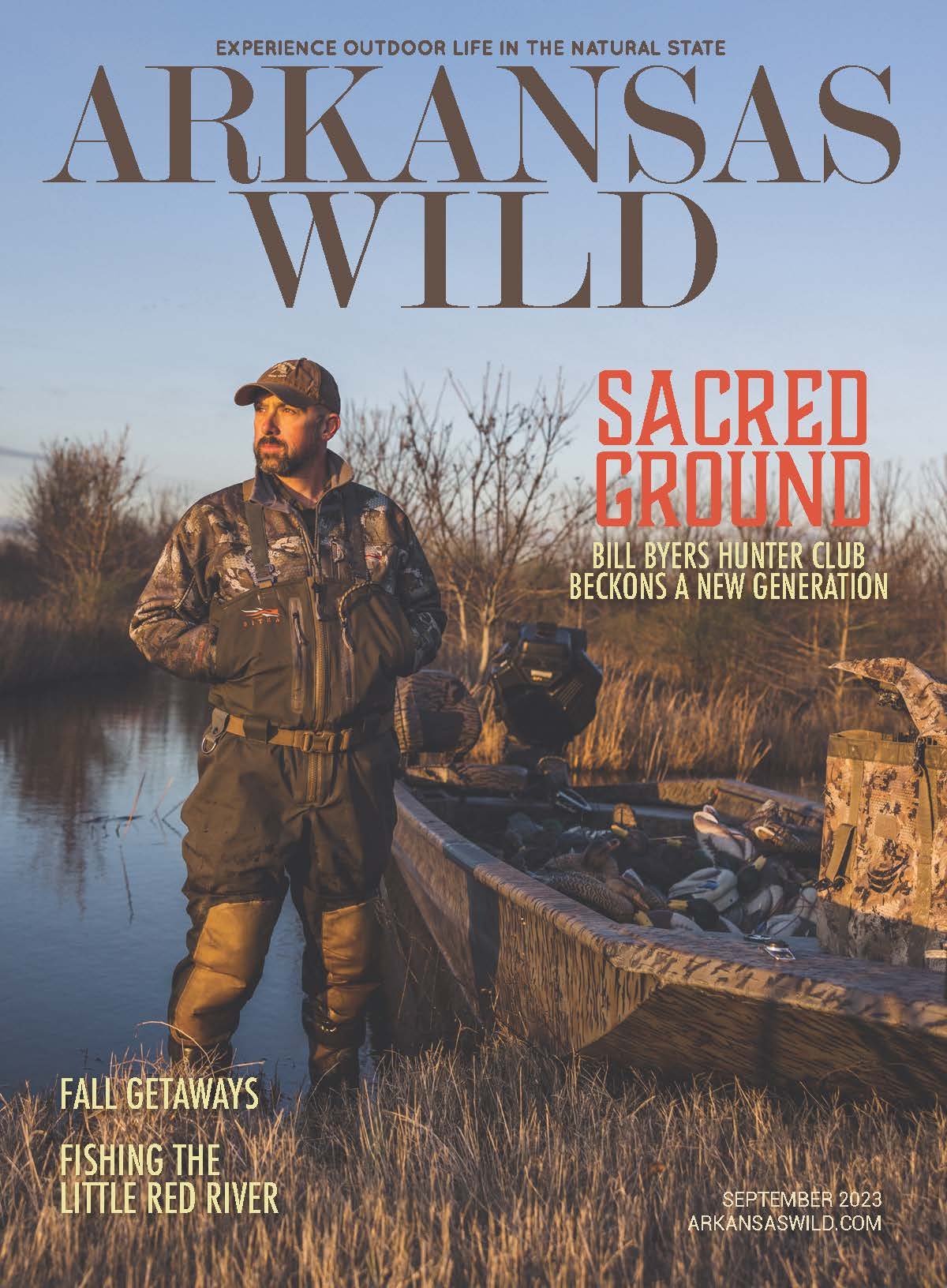

Jeff Glasbrenner shows off his custom-designed carbon-fiber prosthetic leg among the treacherous ice floes of Mount Everest.

From the age of eight, when a farming accident left him a below-the-knee amputee, Jeff Glasbrenner has not only had something to prove—he’s had incredible success in doing so. The three-time Paralympian and former professional wheelchair basketball player has always insisted on pushing his body to its limits, competing in (and finishing) more than two dozen Iron Man competitions, setting scoring and rebounding records (63 points and 27 rebounds in one game), and, most recently, tackling the tallest mountain peak in the world: Mount Everest.

When I caught up with Jeff, he was just returning from the Sundance Film Festival, where he had been helping promote Capturing Everest Virtual Reality, a new project that will allow everyone an immersive experience from the comfort of a VR headset. He’s direct and straightforward about what motivates him:

“People see my disability and not my ability,” he says. “I want to show people what I can do.”

Jeff splits time between Arkansas and Colorado, and says he’d never done any climbing before moving to Denver. “I went to the Grand Tetons two years ago,” he says. “I got into a group by chance, and there I was, no experience with altitude, climbing. Being an endurance athlete made that easier, but there were still many things to learn.”

There were multiple obstacles to surmount in the lead-up to Jeff’s trip to Nepal. The first, and perhaps most vital, was developing a prosthetic leg that could serve two functions: be light and flexible while insulating his leg where it attached. He worked with a doctor in New York to develop a one-of-a-kind leg that would allow him to tackle the extreme conditions of Everest. The result was a $60,000 carbon-fiber and carbon-foam prosthesis. “It’s unique,” he says. “But the research and development that went into it will advance prosthetics moving forward.”

Once his prosthetic leg was in place, he then had to convince a guide service to work with him. “Finding a guide was a challenge,” he says. “Most guide services considered me quite a liability due to being an amputee—plus not having a lot of experience. I finally connected with Madison Mountaineering, and they gave me a shot.”

That shot required Jeff to travel to Argentina and scale a 22,000-foot peak there in order to prove he had the skills to tackle the Himalayas. “Once they knew I had developed good climbing skills, they agreed to take me on for Everest.”

“I left on March 31, 2016 and two days later I was in Katmandu,” Jeff says. After a few days of touring the city, Jeff and his team got ready for the main event.

“They lined us up like gym class,” Jeff says with a laugh. “The sherpas got to pick who they wanted to climb with, and of course, I was picked last.” The skepticism of the native guides was quickly put to rest during the preliminary obstacle courses and practice climbing required of those wishing to summit Everest. “After being the first one through the obstacle course, my guide realized I could do this.”

Part of the preparation for climbing Everest involved obstacle courses in the Himalayan foothills (top). Dangerous ice floes and high altitude combined to create an enormous challenge for everyone on Jeff’s team. (Facing page) An exuberant team celebrates their ascent of the world’s tallest peak. Jeff (bottom) had to wear up to 20 pairs of socks to maintain the fit of his prosthetic leg after losing an enormous amount of weight on the climb.

The actual climb of Everest was a combination of grueling climbs and patience. Of particular concern to Jeff was a section of ice floes that had a tendency to break and crash to the ground at unpredictable moments. “We started our climb at 10 p.m. just because that’s when the ice is the most stable. Still, there were instances when massive amounts of ice would crash right in front of us. You’re playing the odds, really,” he says.

His greatest moment of doubt came during his first night at base camp—19,500 feet above sea level. “The air is so thin. I woke up that night feeling like I was drowning, gasping for breath. Your body and mind are just stressed and it takes a while to acclimate.” Lucky for Jeff, he endured—with some help from a teammate—and woke the next day ready to climb again. “That was the only time that happened, thankfully. I just view it as another way my body got stronger,” he says.

After making it from base camp to camp 2, Jeff’s team had to contend with massive storms, waiting for six days until they could continue the climb. This resulted in something that affected Jeff more than anyone else on the climb—weight loss. “They call it the Everest Diet,” he says with a laugh. “I lost 20 pounds in those six days. And the thing about being an amputee, my leg is custom-designed to fit me at a certain weight. Losing weight means this device I depend on doesn’t fit as well anymore.” He had the foresight to pack extra socks to make up for the weight loss—a lot of extra socks. “I normally wear a pair over my stump, and after that week I was wearing 20 pairs.”

Taking the best weather-window they’d had still meant traveling to the oxygen-deprived “death zone” of Everest in white-out conditions. Their initial plan to make a seven hour climb with eight hours of oxygen turned into a grueling journey of 12 hours—in an area of the world where rescue is impossible. “We had to spend an extra night in the death zone,” Jeff says. “It was like being on another planet.”

Finally, after weeks of maneuvering the cliffs, 10,000-foot drop-offs and storms of world’s tallest peak, Jeff and his team made their summit push, utilizing a method of climbing that required taking a single step, then resting for three breaths. “When we got to the summit, I spent 25 minutes there; just reflecting on everything—and the 1,200 miles of visibility such a height provides you.” Of course, then came the climb down.

“We always say, ‘Don’t make it to the peak and miss the point,’” says Jeff. “I had to get back down so I could see my family. Most accidents happen on the way back—people are tired, there’s limited oxygen and food, and people take risks.” Finally, after six weeks of making Mount Everest his home, Jeff arrived back in Katmandu, tired and relieved—and also a man who had conquered the world’s highest peak.

For Jeff Glasbrenner, Everest was just another example of pushing himself to every possible limit—and not letting the loss of a leg mean the loss of any experience. He’s going to be one of the first amputees to run the Moscow Marathon next fall, and has several Iron Man and speed climbing ascents in Europe planned as well. “I’m always trying to be the best I can be,” Jeff says.

For more information on Jeff’s Everest climb, his public speaking schedule and a link to buy his book, The Gift of a Day, visit Team Glasbrenner’s website at teamglas.com.