Rich in history, Bill Byers Hunter Club welcomes a new generation of hunters.

By Dwain Hebda Photography by Novo Studio

In many families, home is as much a state of mind as an actual place. People pass, kids move away and buildings change hands, leaving few constants through time save remnant memories of sights, smells and sounds of days gone by.

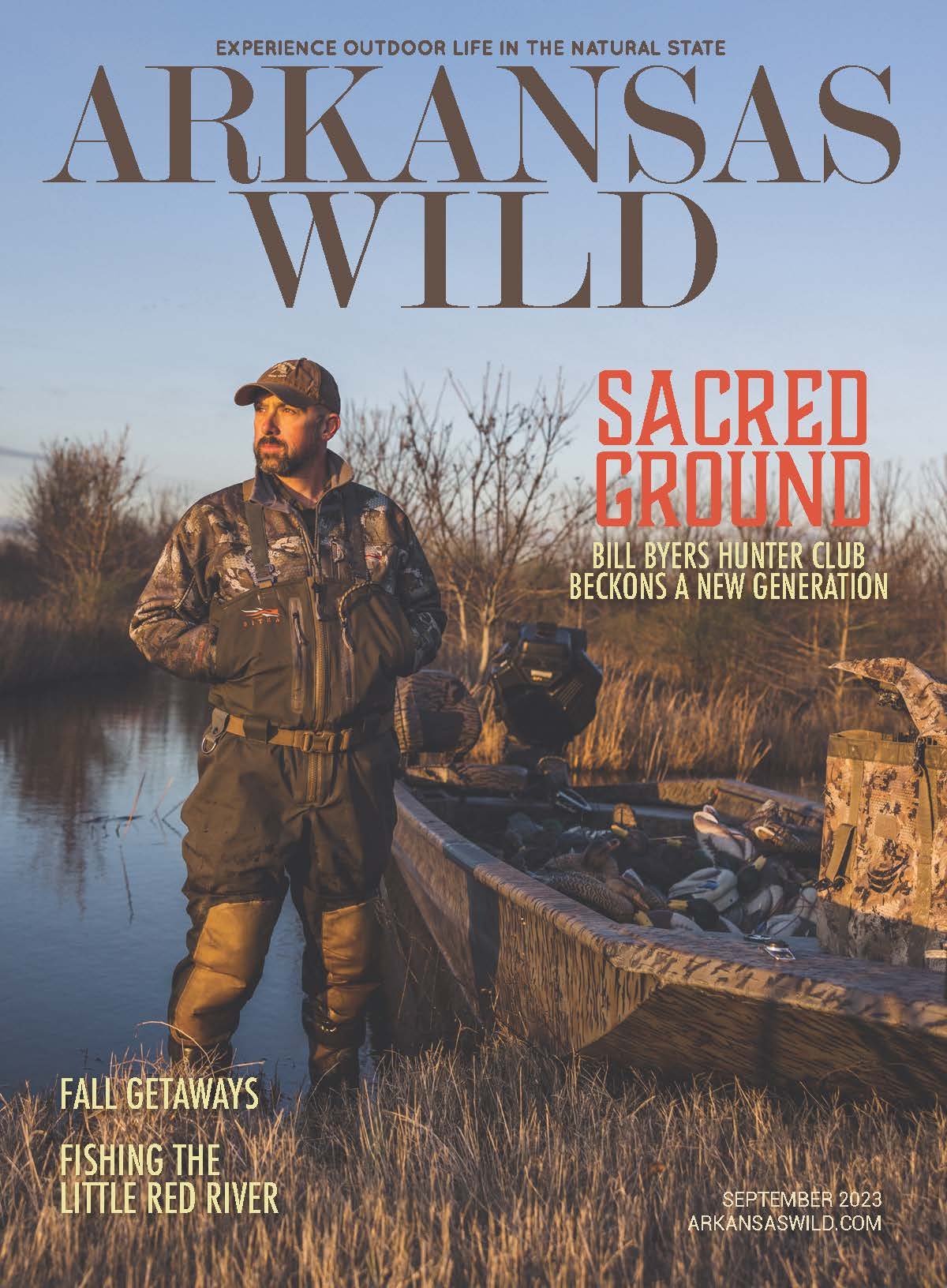

Not so for Cason Short. At least five days a week he leaves his house and comes home, working the third-generation land that is Bill Byers Hunter Club in Hunter (Woodruff County). There, he tends the 3,000 acres that produce rice and soybeans during the growing season and delight scores of hunters during duck season.

“We still are an active farm involved in ag production,” Short said. “I guess, to put it colorfully, I am a land manager for ag production and for duck hunting.”

Any independent farming operation lasting seven decades is doing something right, but business and passion are often two different things, as Short acknowledged about his ancestral land.

“Farming is something that we do and it is important,” he said, “but it’s ducks I’m really passionate about.” —Cason Short

By all indications Short’s grandfather, Bill Byers, felt the same way. A descendant of the Byerses who settled around Lodge Corner in Arkansas County before the Civil War, Bill drove his stake into the Delta soil with 1,200 acres of green timber in 1953. He proved a visionary for his day, installing an extensive system of levees that helped move water efficiently.

“He had grown up around commercial duck hunting and rice production, and so he saw water as an asset,” Short said. “When he came to our part of the world, he knew that he could pay for that land. He could subsidize it through duck hunting, but he also recognized the value of water.

“He was very far ahead of his time developing water control structures in the desire to manipulate water, move it from one place to another. A lot of things we now take for granted hadn’t been done before in the ’50s and ’60s”

Byers’ place quickly became a prime spot for hunters, and he’d soon add 1,800 acres and adopted other forward-looking practices that have survived to the present day.

“What we call our rest pond is a 230-acre field and I believe it has been our rest area since the ’50s,” Short said. “My grandfather started it and recognized how valuable that was and how successful it was, and we continue that practice today. We don’t drive around it and we try not to hunt next to it. We limit as much access to it as possible for the season.”

Byers had built a duck hunter’s paradise but had to pivot in the 1960s when a short season and one-duck limit came along. To pay the bills, the painful but necessary decision was made to clear timber for rice farming. The duck side of the ledger waned until Short’s father, Charlie, came aboard in the mid-1970s.

“The duck hunting had not gone away, but it definitely had taken a back seat to farming at that point,” Short said. “My father got involved and with my mother and my grandfather at that time they decided to get it back where it was in the ’50s and ’60s.

“We were pretty lucky. The government had a lot of subsidies for what they called set-aside grounds where they would pay you not to farm, and you could plant cover crops. Through the ’70s and ’80s we were hot cropping as you would call it today; we would grow milo and leave the whole thing standing for ducks on that set-aside ground. It made for some amazing hunting.”

Short started guiding hunts at 14, and remained involved in various capacities even as he was educated in Memphis and earned a construction management degree from Mississippi State. In less than a year between 2009 and 2010, he’d lose both his grandfather and his dad, putting the legacy of the family operation squarely at his feet. Since then, he’s continued the tradition of conservation-minded hunting while expanding amenities to include sporting clays and bass fishing.

“Our lodge is the original building from 1953. It’s been added onto a number of times, and I think people really enjoy the history of that,” he said. “On the food side of things, we definitely upped the quality of what we offer and the items we offer on the menu. That’s part of the experience now. Something else we offer that we didn’t a few years ago are afternoon specklebelly hunts. We are planning to get involved in upland bird hunts in the future for afternoon activities to round out the experience.”

“Experience” is a watchword Short pays a lot of attention to these days. While the majority of his hunting clients are, in his words, “Joe Duck Hunter” from Arkansas, his vision for the future has led him to dabble in new tactics to broaden his reach.

“To put it bluntly, duck hunting has been a middle-aged, white male-dominated sport and it still is,” he said. “But we have had hunts with a group I guess you would label as social media influencers. They are an extreme minority in our sport, but that’s been kind of interesting and fun.

“Our clientele base has changed a little bit in recent years and I think social media is driving some of that. We deal a good bit with other partners, companies like Remington that have started sending out writers from different parts of the country. I’m not sure social media really books any hunts for us but our customers do follow it and they do pay attention.”

It’s a unique spot Short finds himself in these days, on the seam between his forefathers’ generation and that of his children, ages 2 to 9. Helping reshape the land he knows so well to be enjoyed in new and different ways is the path forward, but translating 70 years of spirit and tradition in an Instagram post takes a little doing. Fortunately, there are plenty of stories to tell, like that of his grandfather’s funeral.

“When my grandfather passed away in ’09, he was buried on the opening day of duck season,” he said. “My mom was a little bit irritated with us that we went hunting that morning, but it was pretty neat in the midst of all of that to be able to go with the pallbearers and people who were there and enjoy what he had done and to celebrate his life. I think that’s what he would’ve wanted.”