The Bowfin

The Fish That Won’t Stop Spawning Stories

By Mark Spitzer

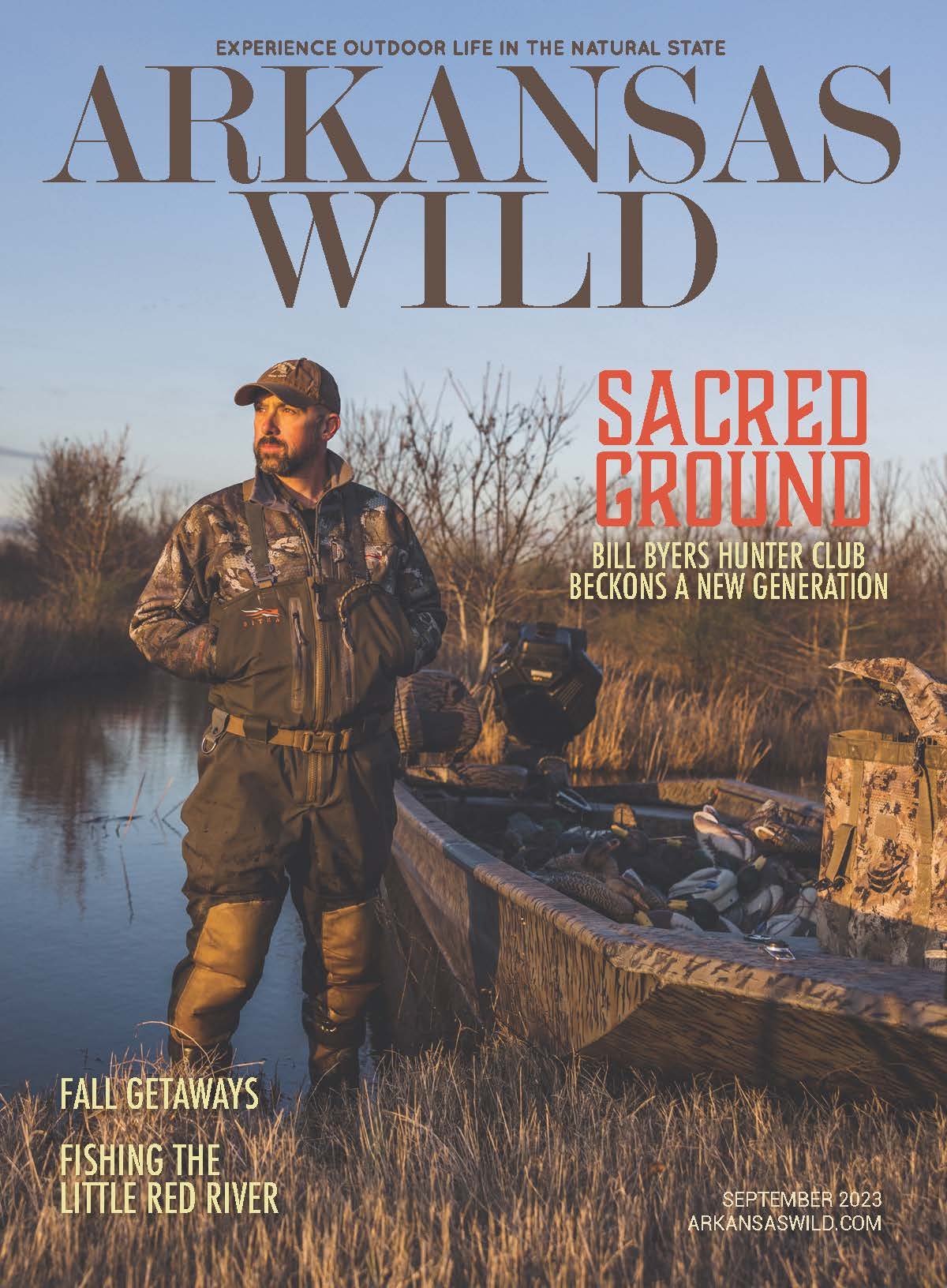

Mark Spitzer holds a grinnel caught at Grassy Lake near Mayflower, Arkansas.

Bowfin, or “grinnel” as they’re called in Arkansas, are a prehistoric, bone-headed, air-breathing, eely-finned, monster-fanged fossil-fish dating back to the Jurassic period that fishermen love to hate. Grinnel are right here, right now, swimming all over the state. Yet for the million-plus years they’ve been around, nobody knows much about them. In fact, bowfin biologists are just discovering that there are actually different genetic-specific populations—so now there’s even more to be freaked out about.

They steal bait, break fishing poles, get in the way of crappie and bass, and cause general havoc when they’re caught. They slap back, smack tackle all over the place, and because they’re pure muscle, they’re almost impossible to hold. But that’s why, on rod and reel, they’re epic to do battle with. I once fought one more in the air than in the water. That bowfin kept leaping six feet into the sky and pealing out line. It was like fighting a berserk tarpon pumped up on steroids and road-rage and bathtub crank—which is why they should be considered “sport fish” rather than “garbage fish.”

That thought aside, bowfin don’t get much longer than three feet or weigh more than 20 pounds, but that’s the size of a hefty salmon. They’ve got these unearthly, barbley nostril-nozzles that add a dragon-like quality, and when it comes spawning time, the males turn a bizarre shade of neon lime-green—which is a defense mechanism, because who wants to eat a fish glowing from nuclear waste?

To Dine or Not to Dine (On Bowfin)

But the bowfin’s most effective defense mechanism is the fact that they’re the worst-tasting fish in existence. I’ve tried various methods with nothing but failure. The last time I beer-battered one, it tasted like a combination of what I can only imagine as soggy cardboard and fermented possum.

What bowfin are good for, though, are stories. Like the story my friend the wildlife writer Keith “Catfish” Sutton once subjected me to. Seems there was this fishing camp down south, and every day the fishermen went out and brought back fish, and the camp cook, Ol’ Cooky, well, he’d cook ’em right up. But one day Ol’ Cooky decided he was gonna go fishing. So he went out and caught himself a grinnel and brought it back. It was 10 pounds, and the fishermen made fun of him. But Ol’ Cooky put that grinnel on the grill and he put onions and spices on it--and the fishermen started coming around. Their salivary glands got excited, and everyone wanted some. But Ol’ Cooky, he told them, “I’m gonna eat my share first, and then y’all can have some.” So they watched as he ate the whole dang fish, and then he was done, and nobody got nothing.

This story, of course, was told in the spirit of the Ozark oral tradition, so it took half an hour to tell. When it ended, I fell right into Catfish’s trap. “What?” I cried. “You expect me to believe he ate a ten-pound fish all by himself?” But Catfish, he just sat there grinning back.

Robert “Turkey Buzzard” Mauldin shows off his grinnel catch from Grassy Lake.

Speaking of cooking bowfin, have you heard the one about the recipe for bowfin on a plank? You take a cedar plank, soak it all night in pickle juice, place your bowfin filets on it, sprinkle with salt and pepper and lemon juice, then cook low and slow on an open fire. When it’s done, you throw out the fish and eat the plank.

But seriously, folks, my fishing pal Turkey Buzzard once tried his hand at cooking grinnel. We’d caught four big ones in Point Remove and he was set on finding out if they were really that horrible. He flayed eight flanks, and being a chemist, he decided to soak them in saltwater overnight to leech out any impurities. In the morning, he stuck his hand in the bucket, and to quote him verbatim, “It wasn’t anything but goop! Just pure liquid! I had to throw it all away.”

A few years back I was researching bowfin for a fish book and I needed to catch one to complete the chapter, so I called an emergency meeting of our “Fishing Support Group.” So Minnow Bucket, Pancho Narwhale, Turkey Buzzard and I set out on Grassy Lake in two canoes. We threw out a bunch of noodles and jugs and paddled away. A few hours later, we went back. We caught one nice bowfin which had pretty much given itself a heart attack by hauling that jug all over the slough. It wasn’t going to make it, so Turkey Buzzard decided to get it stuffed. When it came back from the taxidermist, though, there was a red spot painted on its tail.

Now here’s the thing about bowfin tails: The males have an ocellus, which is commonly called an “eyespot.” It’s basically a black splotch surrounded by a blazing orange-yellow corona. Scientists speculate that this defense mechanism makes predators think they’re looking a larger fish in the eye, so they don’t attack. But in the 40-odd years I’ve known bowfin, I’ve never seen a red spot in addition to the ocellus.

We ribbed Turkey Buzzard for years. Nevertheless, he still insists that the grinnel he now proudly displays on his wall has unique DNA. Even to this day, he continues to argue that the photos he showed the taxidermist are evidence of a natural mutation. But the more he makes that argument, the more we laugh.

This case, however, is now closed, because I recently found a picture of Turkey Buzzard showing the other side of that fish, which doesn’t have a red spot on it. Meanwhile, the eyespot appears on both sides, which means that while flopping around in the boat, that bowfin picked up some sort of red speck or a drop of blood that was forever immortalized in the taxidermied fish.