Living in Arkansas is a privilege for those who enjoy the outdoors. We have access to a beautiful, diverse range of outdoors spaces, from mountains to woods and fields to rivers. This year’s class of Legends is also diverse. Nominations range from forest stewards to the tourism industry to entrepreneurs to photographers. No matter how they do so, those who participate in the conservation and promotion of our natural spaces have amazing stories to tell.

Arkansas Wild is proud to recognize our fourth annual Legends of the Wild. These five individuals— Larry and Shirley Aikman, Bill Barnes, Tim Ernst, Zach McClendon—have made contributions to the Arkansas outdoors that can be felt statewide, and in the following pages we pay tribute.

By Lacey Thacker

Photos by Novo Studio

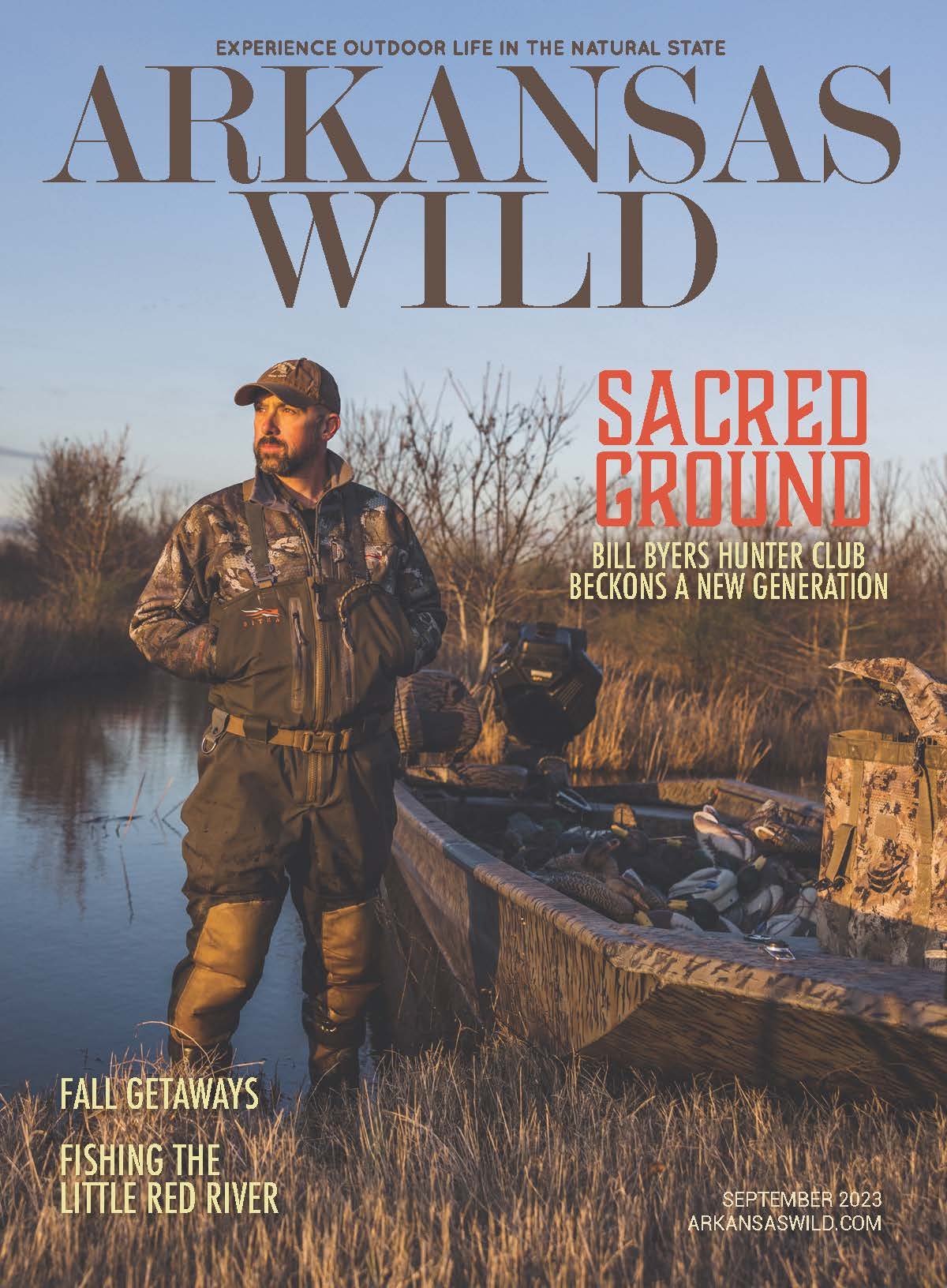

Zach McClendon relaxes on the porch of his cabin at his hunting camp in Tillar.

Zach McClendon

By Richard Ledbetter

I got invited to meet Zach McClendon after he read my first novel, The Branch and the Vine. A mutual friend introduced us and Zach immediately made me feel like an old friend. I quickly recognized what a remarkable and multi-faceted individual Zach truly is. His interests range from energy conservation to finance, sportsmanship, manufacturing, gardening, wildlife conservation and even jewelry design. His most obvious industrial pursuits include MonArk Boats, SeaArk Boats, SeaArk Marine, Drew Foam, Concrete Foam Structures and Saline River Diamonds. He’s proven an over-achiever most his life, becoming an Eagle Scout at age 16, in 1953. Along with his father, Zach, Sr. and Norris Jenkins the trio founded their first aluminum boat company, MonArk, in 1959, when Zach was only 22.

McClendon recalls MonArk’s humble beginnings. “I was attending the university in Fayetteville and my dad called one day because he knew how much I loved boats. He said, ‘There’s this fellow Norris Jenkins who worked for Duracraft. He has a one-man shop where he built himself a jon boat and made another for a friend. We might put something together with him.’ I said, ‘Yes, sir! When do you want me home?’” Zach’s daughter, Robin, added, “They began building jon boats and Zach, Jr. would load them on an old truck and sell them wherever he could—bait shops, hardware stores and even mom and pop filling stations. His dad told him, ‘Don’t come back until you’ve sold them all, and he wouldn’t.”

She added, “In the early 60s, the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission asked if we could build a cabin on a 16-foot jon boat. We did, and that’s how the commercial side began.” With Zach at the helm of both branches, Robin says, “We built a lot of boats in the 70s for the oil and gas industry, and later we did many projects for the military.”

As Zach turned his attention to other entrepreneurial pursuits, his son John took over operation of the marine division in 1998, while his daughter Robin filled the president’s seat for recreational in 2001.

Until the end of 2016, McClendon was Chairman of the Board of Directors for Union Bank of Monticello and Warren for over four decades. On January 15, 2017, more than 100 regional movers and shakers turned out for a reception in Union Bank’s downtown Monticello lobby to wish their longtime friend and banker the best. Current State Bank Commissioner Candice Franks said on the occasion, “I’ve known Zach for 36 years. He is a wonderful community banker who always gave back to his hometown. It’s great to have bankers like his team in Southeast Arkansas.” Further confirming McClendon as an integral part of Arkansas banking, Governor Asa Hutchinson appointed him to the State Banking Board in 2015. Current Union Bank Chairman John McClendon said of his father, “He had almost a full career with MonArk and Drew Foam before coming to Union Bank. He goes to bed at night and gets up in the morning thinking of something new to create. He’s been a driving force for growth in Monticello for decades. Zach’s a broad-spectrum guy who looks wide and far at the bigger picture rather than the minutiae. I prefer to get involved with the details. That’s why we make such a good team.”

The other side of McClendon from his business acumen is the naturalist. Seeking to fulfill an annual family tradition a few years back, he was strolling along the riverbank near his camp on the Saline, searching for some natural materials from which to fashion a birthday gift for daughter Robin. McClendon came across a pile of empty mussel shells where a coon had eaten dinner. Taking them home, he began to polish and form the delicate shells into mother-of-pearl earrings. Robin was so impressed with the gift she showed them to friends who were soon clamoring for a similar pair. Since that eventful day, Saline River Diamonds became a burgeoning operation crafting and distributing bracelets, necklaces and earrings.

One of McClendon’s proudest accomplishments is the founding of Squirrels Unlimited. He said, “We have several goals for the promotion and conservation of this most versatile creature, one being preservation of squirrel habitat. Besides striving to protect hardwood forests in general, we attempt to educate timber companies on the benefits of leaving old, hollow, hardwood den trees that merit little to no commercial value as brooding centers for generations of squirrels. Our membership continues to grow every year.” An offshoot of Sq U is the World Championship Squirrel Cook-Off held in Bentonville each September since 2013.

His environmentalist side was recognized with his 2010 induction into the AGFC’s Outdoors Hall of Fame and the 2013 Arkansas Wildlife Federation’s Harold Alexander Conservationist of the Year award for a lifetime of contributions toward wildlife.

McClendon is enrolled in the USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program, setting aside large swaths of marginal land for wildlife, as well as supporting Ducks Unlimited, Delta Waterfowl, Nature Conservancy, Arbor Day Foundation, Quality Deer Management Association and the NRA.

In his typical unassuming manner, he concluded, “I haven’t really done anything. It’s the people who have been with me for the ride that helped make all this happen. I’m so blessed to have such wonderful, supportive, hardworking children to bring my dreams to life.” It makes me proud he read my book and that led us to an interesting and enduring friendship.

Larry and Shirley Aikman pause on a walk through their pine tree farm in Blufton.

Larry & Shirley Aikman

When we first chat about their farm, Shirley Aikman asks me what I know about tree farming. “Well, I know it involves trees,” I respond. With her typical humor, she teases, “Well, you’re on top of it, aren’t you?”

Shirley and Larry Aikman’s marriage started in Blufton, Arkansas, but their decades in the Army took them all over the world. In fact, they moved 28 times. Their last assignment was in Arkadelphia, where Shirley taught fashion merchandising. She’d previously worked in design while they were in Hawaii, so she had practical experience to share with her students.

Though the Aikmans had intended to retire after Arkadelphia, Larry was put on the full colonel list, so instead of retiring they went to Washington, DC for three years. It was not Shirley’s favorite place. When their three years were up, she said, “I’m moving back to Arkansas!” Larry came too.

The Aikman’s home is meant for a family. A large house, it has a cabin-like exterior of natural stone. Shirley says they had a house very similar to this one before they went to Washington, so it was built to somewhat replace that one. The interior is homey and the walls covered with bookshelves that are full of titles. They’ve been back in Arkansas for about twenty-five years, and Shirley explains that while the home is somewhat large for their needs now, for many years it served as a place the entire family—kids and grandkids—could gather.

When they initially retired, they spent the first few years going to “tree meetings,” and eventually, they decided to plant their property in timber. “You can grow cattle or you can grow trees,” the Aikmans tell me, so they went with trees. Currently, they’ve got about 400 acres of pine plantation, the majority of which were planted in the year 2000.

The Aikmans were named Forest Stewards of the Year for 2017, and when Shirley pulls out their management plan, it’s clear why. Their plan combines several objectives into one plan, from wildlife management and recreation to water management. Then, of course, there’s the timber. For the Aikmans, tree farming isn’t just about profit—it’s about healthy and productive management of natural resources. Eric Myer, district forester, says of the Aikmans, “They take good care of their property. They keep up with current events and programs to help land owners, and they also work with the NRCS to make improvements. They manage each area according to best management practices.” Stan Garner, cattleman and retired district conservationist with the Natural Resources Conservation Service, says of Larry Aikman, “He’s very innovative and forward thinking, and he has an extremely positive attitude.”

As we visit, I look out the window and notice not only the native plants in their yard, but the bird feeders. Larry shows me a beautiful photo of a bird taken from the window, and Shirley shows me the painting she’s done of the same bird.

As we drive through Blufton, Larry points to several homes and notes which of his children now lives in each. They tell me, “We consider ourselves very blessed that of three kids, all are retired right on our doorstep.” An impressive thing, to be sure, given that each of their children also moved to work outside of Blufton and has made the choice to return to the family home. Though the elder Aikmans are still involved, their son Larry has taken over most day-to-day operations.

“Do you feel like closing the gate?” Larry asks Shirley as we pull up to a section of their tree farm. “I’ve often wondered what you’d do if I said, no babe, I don’t really feel like doing that right now,” Shirley responds dryly. Larry says, “I guess I’d get out and close it,” as Shirley reaches for the door handle.

Tree farming has changed somewhat over the last twenty-five years. The Aikmans used to plant seedlings, but today they plant containers, which have a higher success rate and are easier to plant. Additionally, they explain that hardwood is becoming more valuable, though a hardwood tree farm is still somewhat impractical unless you can figure out how to definitely involve future generations. As we drive through different parts of the property, the Aikmans point out areas in varying stages. Some of the pine has been recently thinned to encourage sturdier growth. Some areas have more pine needles that have dropped, creating easy-to-walk-through paths under the trees. We pass a blind, and Larry notes that they get some great deer hunting on their property. While much of the community used to be allowed to hunt their land, they’ve curtailed it to only family in recent years, in defense of the trees.

In one spot, we stop and exit the vehicle to observe a pond. They’ve recently cleaned it out and tidied up the edges. It’s a beautiful spot, and one local wildlife has obviously found—there are tracks everywhere, along with sound of birds. The Aikmans tell me their daughter-in-law plans for a gazebo overlooking the pond that the entire family can sit and enjoy—making this, like much of what they do, a family affair.

Tim Ernst frequently walks Round Top Mountain Trail near his home in Jasper to observe and photograph.

Tim Ernst

Tim Ernst is arguably the most well-known Arkansas landscape photographer, but he’s also developed a reputation over the last thirty or so years for his guidebooks detailing trails across the Ozark and Ouachita mountains. In fact, they’re considered an authority for both beginners and seasoned hikers alike, as they’re some of the most accurate, detailed books available.

Tim meets me and the photographer at the base of Round Top Mountain Trail trailhead, on highway 7 just out of Jasper. He’s driving a large van that he recently purchased, and comments later that it’s wide enough to use a forklift to put pallets of books into the back. And that’s good, because it’s coming up on the holiday season of November and December, when he, his wife and his in-laws will make several trips around the region to present slideshows of his photography and sell corresponding books.

In 1981, Tim was helping build the Ouachita Trail. There wasn’t yet any information about it, so he began writing. In 1983, he sold his first article to Backpacker magazine, and with the publicity it brought he quickly sold 10,000 copies of the guidebook. Eighteen guidebooks later, he’s still going strong. “I was with the Forest Service in Wyoming and the sign would say 500 yards to the top, but it was really two and a half miles. There was just a lot of inaccurate information,” Tim says.

It didn’t take him long to realize that information sold—particularly his good information. Because Tim uses a surveyor’s measure to walk off trails, the distances listed in his guides are exact. While he walks the trail, he records himself talking about the incline, views of interest, the weather at different times of year, how to get from point A to point B, and GPS coordinates. When people purchase one of his guidebooks, they get a comprehensive text detailing all this information and more.

Tim and his wife recently moved “to town” from their cabin in the wilderness. The downside, Tim says, is that their phone has reception. A result of this change in accessibility is demonstrated in a recent phone call. A man was lost on a trail, and, as he was using one of Tim’s guidebooks, he called the man himself. “Well, what does the guidebook say?” Tim asked the man. “It says call Tim and he’ll help!” With a little backtracking, the man did indeed find his way off the mountain.

Every year, Tim produces a new picture book of Arkansas landscapes, flora, fauna and wildlife. Though Tim is certainly an introvert, he said he really looks forward to going to public libraries and other institutions around the region to show slide shows of his most recent picture books, and the bigger the crowd, the better. He enjoys answering questions about photography, trails and his books in general. An audience member once asked if he’d hiked every trail in his books, to which Tim responded, “Well, yes. Why would I write about anything I hadn’t done?” Tim is a passionate outdoorsman—he not only hikes and photographs, he also hunts regularly. He’s never been seriously injured while outdoors alone, though he mentions a couple of twisted ankles that weren’t too fun. He’s discovered, though, that if he just walks on them, the pain diminishes and he’s able to walk out.

Tim’s initial plan wasn’t to become a photographer—he was going to go to Arkansas Tech on a swimming scholarship to become a forest ranger. But, the ratio of men to women was 20 to 1, which didn’t sound too good at the time—and, more importantly, he wasn’t convinced of his career prospects as a forest ranger. So he chose the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, where he majored in environmental science, though he says he really majored in the darkroom. While in college, his first job was photographing sorority girls. Even today, Tim says, he’ll run into a woman who remembers him and who’ll ask, “Say, weren’t you that photographer…?”

Tuition was certainly less expensive in the 70s, but it’s still noteworthy to point out that Tim made money to pay for college in an unusual way: by picking up and selling black walnuts. He got five cents a pound. That’s a lot of walnuts.

Tim has been taking pictures of some places for years, so when I ask him what keeps it interesting, I laugh when he responds, “Paying bills!” He lets out a small chuckle and then says, “Things are always changing. It never looks the same. I haven’t taken the best picture of Hawksbill Craig that I can, yet.”

On the way down the trail, we pause at an oak tree that’s tilted at an angle. At first it appears as though it’s uprooted slightly, but upon further inspection it’s clear: the rock on top of which the tree has grown has broken off, changing the angle of the ground. The tree itself is as strong and rooted as it’s been. Referring to the changing season, Tim says, “That’ll be a nice picture, here in about two weeks.”

Bill Barnes enjoys walking out to the point overlooking Lake Ouachita at Mountain Harbor Resort with his dog, Harbor Dog.

Bill Barnes

Bill Barnes is a widely-recognized name in Arkansas tourism. President of Mountain Harbor Resort; Iron Mountain Lodge and Marina; and Self Creek Lodge and Marina, which make up the Tri-Pennant family of resorts, he has been instrumental in growing tourism in Arkansas.

Bill’s list of honors is long, including 2001 Tourism Person of the Year and member of the Arkansas Hospitality Hall of Fame. And that doesn’t even touch his numerous civic and community contributions. Bill serves on several boards of directors and commissions, including Arkansas Sheriff’s Youth Ranches; State Parks, Recreation and Travel Committee; and he is the founder of the Arkansas Marine Sanitation program to keep Arkansas lakes clean.

Despite his many years spent growing the resort, he still spends most days working the property. Upon shaking hands, he is genuinely welcoming, and he questions whether a recent guest in our party has been well taken care of. Bill is pleased to hear the answer is yes, but assures the person that if something weren’t right, he wants to know so Mountain Harbor can continue to improve.

As we head out to scout photography locations, Bill and Pati, the lodge manager, exchange a familial half-hug. As it turns out, Pati has been working for Mountain Harbor Resort for over thirty years, and she says she’s not the only long-employed staff member. Many of the staff have been there for nearly twenty. It’s more than a job, Pati says. “It’s everything to us. It’s the reason we get up in the morning.”

Though the resort is thriving today, Pati recalls a time when that was less the case. “I remember buying dishes at the dollar store and trying to make them [cabins] as nice as possible. People kept coming.” Today, Pati says, Mountain Harbor means everything to Bill. “We’re really proud of our units now and what we’re able to offer our customers,” she says.

Bill was born in Wyoming, but his family has deep roots in Arkansas on his mother, Katheryn’s, side. She and his father, Hal, from Oklahoma, met when he was in Arkansas for college. After World War II, they followed Hal’s best friend to Wyoming, where Hal began work as a mineral rights lawyer before going in to shoe sales to support his family during the Depression. On vacation in Arkansas one year, Bill's father found land for lease from the Corps of Engineers. On a whim, he applied for the lease and was awarded it in early 1955. That land was on the newly-filling Lake Ouachita.

Bill was 9 years old when he moved to Mountain Harbor with his family. Though fishing wasn’t necessarily his favorite pastime, he did love to go out on the water. He had a little flat bottom boat, and he would get a peanut butter and jelly sandwich then go float around the lake. It was only a few short years later, when Bill was about 21 years old, that he took over the resort.

When it’s time to take photos, it’s by the lake that we decide to meet Bill. As he walks down the hill from the office, I comment to Pati on the interesting boat moored at the marina. She explains that it’s a motor life boat, part of the Joplin Volunteer Fire Department. When Bill walks up, he continues the explanation with a smile. He started the JVFD over thirty-five years ago, and he has served as its chief ever since. The boat is a 47-foot motor life boat, and it’s part of the response squad that serves as the only fire and rescue squad on Lake Ouachita.

Steve Bowman, an outdoor writer and editor, photographer, television show producer and close friend of Bill, notes that Bill is a “true Southern gentleman” who truly cares about what happens to the people living in his community. During a storm in the middle of the night, Steve, also a Pulaski county deputy sheriff, was barricading a flooded road. Who came along but Bill Barnes—Bill had gotten word that the home of some friends of his was flooding, and he’d come to see what he could do to help. Steve also says, “Bill is a fantastic businessman. To take a little cove on Lake Ouachita and make it one of the premier resorts in the Southeast is pretty incredible.”

Bill also founded the Montgomery County Military Museum, housed on Mountain Harbor’s property, which is where he’s been immediately prior to meeting us. “A guest and his son wanted to see it. It’s free, and it always will be. The kids can walk right up to the vehicles, sit in them. It’s really to honor our military,” Bill explains. It’s important to Bill that kids are able to interact with the memorabilia instead of it simply being relegated to a roped-off corner of a museum, as it makes a stronger impression.

While we finish setting up, Bill introduces his dog, Harbor Dog, to me. “I’ve had him since he was eight weeks old,” Bill says fondly. Harbor Dog stays right beside Bill, following him with his gaze when he’s told to “stay.” It’s clear his favorite place is by Bill’s side, and it’s clear Bill’s favorite place to be is doing what he does best serving his guests at Mountain Harbor Resort.