Black Duck Revival preaches outdoor lifestyle

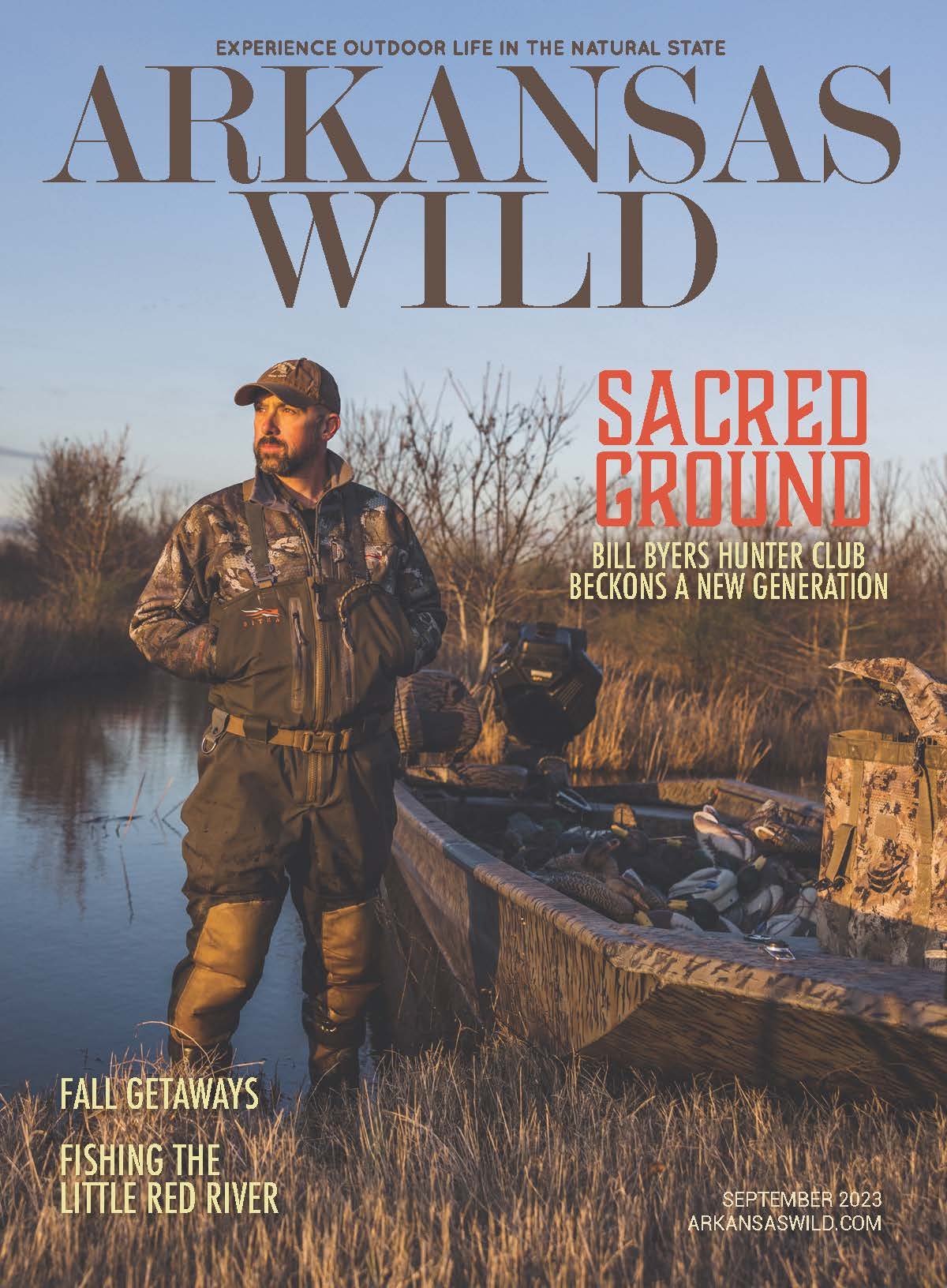

By Dwain Hebda Photography by Marianne Nolley

There’s a lot about Arkansas’s Grand Prairie that defies description. Sprawling out for hundreds of miles in every direction, the land as big and flat as the sky, the area stands in sharp contrast to the hills and peaks of the River Valley, the soaring cliffs farther north or the endless Ozark and Ouachita glades.

Lacking these topographical elements, it’s easy to see the Grand Prairie as one-dimensional, a geological transition zone, faceless as winter crop stubble. Only upon closer examination does one see just how complex and layered a region it is, binding together all that Arkansas is, has been and can be.

It’s a place with which Black Duck Revival and its founder, Jonathan Wilkins, hold much in common. The business, settled comfortably into a former church on Brinkley’s main drag, also defies easy categorization.

“There was no intention to be one thing at the outset,” Wilkins said. “It’s kind of just an organically growing thing. I kind of try not to have a whole bunch of presuppositions about what it’s supposed to be.”

Under Wilkins’ purview, Black Duck Revival exists as a guide service, classroom, processing plant, kitchen, multimedia studio and gathering place. It’s an odd and jarring self-awareness to be everything and yet nothing entirely at once, but that’s precisely the keyhole Wilkins invites people to peek through. Even the name is rife with messaging, though not entirely as it appears.

“A black duck is not a Mississippi Flyway bird, really. They’re really rare in this part of the country,” Wilkins said. “The revival aspect is partly the fact that it was a church. It was also kind of a tongue-in-cheek thing, playing on the racial oddball status of me doing waterfowl in Arkansas.

“But ultimately, the idea was not really for a traditional duck lodge or duck club. This is a place to reinstate human capability. People want to find their own food and beyond that, make the most out of it.”

Bagging birds (specklebelly goose preferred, but ducks welcome, too) is just the appetizer on Wilkins’ full menu of techniques and processes. He also teaches alternative ways to clean the quarry — from mechanical and wax plucking to dry plucking — as well as how to ensure nothing edible goes to waste.

“I teach whole-bird processing,” he said. “We use the feet, we use the neck skin, we use the entire carcass. It’s all part of that idea of a more holistic agrarian association with food and community and all that.”

Black Duck’s rustic luxury and forward-thinking agenda have found a ready audience over the five years it’s been in business. Guests are generally younger, professional and from out-of-state, many looking for a respite from city life and curated new experiences.

“It’s people who are probably in their 30s, people who live in cities or urban environments and are interested in reconnecting with the natural world,” Wilkins said. “Not saying they’re necessarily high rollers, but people who are established.”

Women guests are common at Black Duck Revival, something that speaks as much about the environment here as it does the agenda or programming.

“I think last year I only had one group that was all males. I prefer it when women are here,” Wilkins said. “There’s a different dynamic that cuts down on the false bravado and all that machismo. It’s just a better experience for everybody. With my clientele, everyone’s usually coming here with ingrained humility, wanting to learn and experience something different. It’s not this kind of rapacious domineering school of thought.”

Wilkins said the better-known the club has become for its approach, the more it stands in contrast to more traditional duck clubs.

“Waterfowl, specifically in the South, is a very cloistered community,” he said. “It’s still very much an ol’ boys network. It’s not incredibly welcoming to women, there’s a lot of duck clubs where women aren’t allowed. Hunting in general is an activity that’s passed down patrilineally; it’s fathers and sons and uncles and grandpas. It is not the most inclusive, welcoming activity by nature.”

Wilkins said this heritage has fed the narrative that hunting lacks appeal for minorities, when in fact the percentage of Black and Hispanic hunters compared to white mirrors the general population mix. If Wilkins himself stands out, it’s thanks to his writing and the Black Duck Revival podcast, not for being the only Black hunter in the deer woods or green timber.

For its part, unsurprisingly, Black Duck Revival is comfortably, resolutely color blind, the name aside.

“Black Duck Revival is not and was not intended to be exclusively for people of color. Frankly, the vast majority of my clientele are Caucasian,” Wilkins said. “Initially there was a lot of outward push for it to be this Black duck club, and it’s not that I’m running away from that moniker, it’s that it doesn’t fully encompass what I’m doing. I’m definitely satiated with the organic expanse of it and willing to see what that turns into.”