Duck Blind Confessional

A first hunt inspires awe—and sometimes hilarity

Story and photos by John McClendon

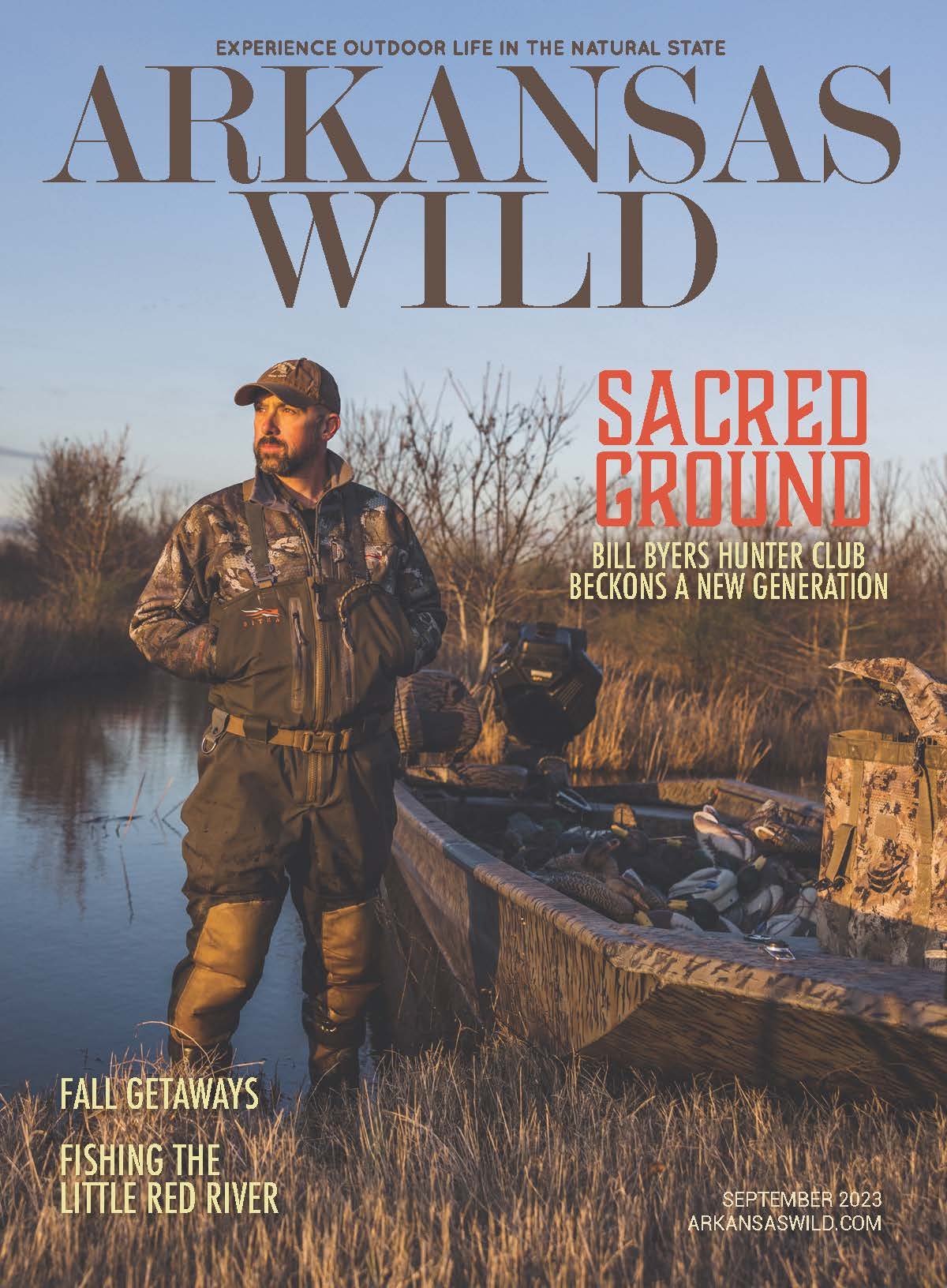

Tom Wingard and Paul Griffin show off their kill in one of several cypress slough blinds author John McClendon uses to entertain business guests.

Like a lot of Arkansas duck fanatics, I have been extremely fortunate when it comes to incorporating hunting into my professional life. I’ve never worked as a paid guide or run any kind of outfitting service, but I have been taking people who were important to our family business out hunting for 30 years.

Hunting is a common way to promote and build relationships with customers, vendors and key employees. No other activity in the world can bond a business acquaintance quite like a morning or two spent together in a duck blind. Sometimes, those trips turn into annual traditions: several of my groups haven’t missed a hunt with me in 20 years—and I took more than a few of them on their very first duck hunts.

It’s a special experience to take someone on their first hunt. Even the crustiest old hunter isn’t immune to the enthusiasm and excitement. There’s a special magic that occurs in someone the first time they see mallards cupping around hard. An epiphany takes place as colorful wings slash through bluebird skies, and a sense of wonder develops at the athleticism of a water-bound retriever’s pure passion and purpose. Every time, it’s as if the newly minted hunter has found some vital piece of life itself they hadn’t even known was missing.

Many of the folks I’ve taken hunting have found themselves similarly awestruck. Those hunts generally ended with smiles and high-fives—but there were a few that got off to a rough start.

I’ve lost count of the decoys sunk by the careless shots of over-enthusiastic guests. One fellow even shot one of my MoJo Duck motorized spinning wing decoys. The wings of the capsized decoy were still slightly turning when he shot it a second time. I guess he didn’t want it getting away.

Anthony Brown and Tom Wingard enjoy the aroma of John’s signature “boat bacon” while waiting on the next flight.

It’s a special experience to take someone on their first hunt. Even the crustiest old hunter isn’t immune to the enthusiasm and excitement.

Another morning, legal shooting time was fast approaching and we all began loading our guns. There were five of us in a 16-foot-long blind; I was on the very end. This wasn’t a group I had hunted with before, and none of them were seasoned hunters—although each man had reported some level of shot gunning experience at dinner the night before. As the moment came to be ready, still and quiet, the gentleman furthest from me seemed to be having some trouble loading his firearm. I leaned forward and shined my light down the length of the blind and immediately saw for myself what the trouble was: he was attempting to load his shells in backwards—brass forward!

Imagine my guest’s surprise when he learned that it wasn’t the shiny metal part of the shell that kills the duck.

Over the years there have been numerous clothing faux pas. Some guests arrived equipped with blaze orange hats or bright red rain ponchos—not realizing that waterfowl are not colorblind. And while I am certainly not a camouflage snob, I did once have to find a way to cover a bright blue zebra-stripe jacket that appeared to be the size of a small circus tent. Such things just don’t blend in too well on an Arkansas rice field levee.

These experiences aren’t unique, and you can always count on duck guides to have the best outdoor stories. One that I heard (but wasn’t present to witness) involved a hunt so cold that a client’s gun froze solid—he pulled back the trigger and nothing happened. Apparently the shotgun had gotten wet, and even though the trigger released the hammer, it was iced solid and wouldn’t fall. The action was also frozen closed, leaving no way to safely extract the shell. The hunters cautiously set the gun aside—pointed in a safe direction—until it thawed. The hammer did, indeed, eventually fall, but too slowly to ignite the shell’s primer.

Another story I wish I’d been there to witness was told to me by a good friend who did not grow up duck hunting—but was a competent outdoorsman just the same. On his very first duck hunt, this fellow joined some friends on a public land hunt which was walk-in access only. He’d borrowed an old pair of waders for the occasion and was eager to experience the “green timber magic” he had heard so much about. About halfway out to the hole, it became apparent the borrowed waders were no longer watertight. The further he walked, the worse the leaks became, and as they neared the setup point, my friend realized that enduring a 30-degree morning in waders full of water was out of the question.

The Trammel family is all smiles after a morning outing with author John McClendon.

Selflessly, he declined assistance and left the group to enjoy their hunt. He headed back in what he thought was the right direction. As any hunter can attest, landmarks in unfamiliar flooded timber can be confusing and very difficult to follow. Before long, he was lost, water-logged, nearly hypothermic and heavily weighed down by the waders—which were now full to the waterline. He determined he could move much faster by abandoning them completely, trekking toward the closest shotgun reports he could hear in just a pair of socks.

The group he found was understandably surprised to see the soaked-and-bootless nomad approaching their set. They pointed my friend in the right direction…then volunteered to walk him out when he arrived back at their hole sometime later after making a full circle.

Even the most experienced among us gets a surprise now and then.

A friend of mine (the saltiest hunter I know) and I once took a client from northern Illinois on a hunt. There are scads of details necessary to properly relate the entire episode, but the climax of the story involves a young alligator clamping onto my friend’s leg as he waded out among decoys. Our patron in attendance—unaware that Arkansas even had alligators—high-tailed it toward higher ground while I worked to free the small reptile from my friend’s leg. He hasn’t been back for a hunt since.

Anyone who has hunted more than a season or two likely has a great story to tell. The social nature of waterfowl hunting lends a jovial atmosphere to the sport. Throw some extreme weather and inexperienced hunters into that environment and you have the recipe for some epic yarns.

It’s just another day at the office for your guide who gets to witness them all.